L’horloge des princes (1555), Antonio de Guevara: “the good which mortal men ought to pursue"

Introduction to the Text

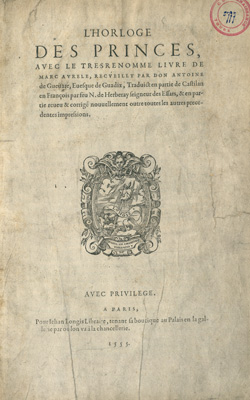

The CRRS book is a sixteenth-century French edition of Antonio de Guevara’s Renaissance bestseller, “The Dial of Princes” (Paris, 1555). It was originally published in 1529 in Seville as an extension of “The Golden Book of Marcus Aurelius” (1528), and thereafter the two were frequently printed together in a single volume. Together or separately, Guevara’s two best known works appeared in around 158 editions between 1528 and 1700, and were translated into most European languages, not only French, Italian, English, and German, but also Romanian and Armenian.[1]

Guevara’s work is an exemplar of the popular Renaissance genre of ‘mirrors of princes,’ advice books for rulers and governors, in this case intended for the Spanish king and Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. The 1555 French edition is dedicated to Cardinal Claude de Longwy de Givry, bishop of Mâcon, by a client eager to establish his credentials as someone whose humanistic learning rendered him fit to serve his noble master. Both lauded the importance of good counsel and education in the making of a virtuous prince, displaying the “courtly bias” that had long since eclipsed the republican ideals of the early Renaissance humanists.[2] Both claimed having undertaken to recover knowledge that had been lost, compiling and preserving the wisdom of the ancients, yet Guevara’s classical sources were largely invented, while for the French editor/translator it was sufficient to offer Guevara’s spurious scholarship as evidence of his own familiarity with humanistic learning.[3] Thus, both the Spanish original and this repurposed French edition may be seen as evidence of a decadent late humanism, no longer engaged in the retrieval of original Greek and Latin texts, their translation and linguistic analysis, but rather exploiting the authority of classical figures to promote some sort of practical wisdom or burnish the writer/editor's reputation.

Dedication to Cardinal Claude de Longwy de Givry, bishop of Mâcon

[1] Thomas James Dandelet, The Renaissance of Empire in Early Modern Europe (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 88. Oana Andreia Sambrian-Toma, "“El Reloj De Príncipes” De Antonio De Guevara: La Primera Novela Occidental Traducida Al Rumano," ed. Antonio Azaustre Galiana and Santiago Fernández Mosquera, Compostela Aurea: Actas del VIII Congreso de la Asociación Internacional del Siglo de Oro (AISO) (2008), https://minerva.usc.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10347/10686/pg_474-481_cc197b.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Horacio Chiong Rivero, The Rise of Pseudo-Historical Fiction: Fray Antonio De Guevara's Novelizations (New York: Peter Lang, 2004), 1.

[2] Charles G. Nauert, Humanism and the Culture of Renaissance Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 184.

[3] Rivero, 1.

Historical Context

Early fifteenth century humanism flourished in Florence and the other Italian city-states, and to the extent that it offered moral and practical guidance for the ruling elites, its ideology was republican and anti-monarchical.[1] This early phase however, was dominated by intellectuals and scholars of Latin and Greek, whose focus was on Latin philology and writing of works of history and literature in Latin. However, the printing press vastly increased the size of the reading public and popularized the classics beyond the relatively small circle of humanist scholars versed in Latin.[2] By the middle of sixteenth century there was flood of vernacular editions to satisfy this demand, but also a departure from the more rigorous scholarship of the earlier Renaissance and the proliferation of pseudo-historical works of fiction whose main objective was to entertain. Guevara’s Golden Book, along with the adages contained in the Dial of Princes, were among the most famous examples of this genre.[3]

By the early sixteenth century, humanistic learning had thoroughly infused the vernacular culture of the aristocratic elites throughout Europe, and a veneer of erudition became indispensable to the self-presentation of any respectable courtier as well as his prince or patron.[4] Practical guides to virtuous living, such as Erasmus’s Handbook of a Christian Knight (1501) were immensely popular, but increasingly less emphasis was given to ideal virtues and more to the types of pragmatic considerations espoused by Machiavelli.[5] Indeed, in the context of the social relations that prevailed at court, advice books dedicated to individual patrons abounded, and for the anonymous French editor/compiler, the “dial of princes” was, as it had been for Guevara, the humanist’s calling card, demonstrating his command of the kind of knowledge that made him useful to his would-be protector.

An Imperial Humanism, a Decadent Humanism?

Despite being one of the runaway bestsellers of Renaissance Europe, Antonio de Guevara’s Mirror of Princes and the Golden Book was criticized by both his humanist contemporaries and modern scholars. Juan Luis Vives was outraged by its racy, vernacular style, but especially its scant regard for historical truth. The humanist project had by the early sixteenth century, when Guevara was writing, been so successful that authors resorted to spurious and even completely invented links with real classical sources in order to, as Vives put it, “gain greater authority for their books […] attributing to Plato, Aristotle, Boethius, Cicero, and Seneca ideas that would not have occurred to them even in a nightmare.”[1] From this perspective, Guevara’s work was a prime example of what a recent historian has dubbed “humanism in its putrescent state.”[2] That may have been so, but Guevara was among the first in Europe to recognize that almost a century of print had given rise to a new and larger readership hungry for works of history, but less discerning when it came to accuracy.[3] On this point, booksellers throughout Europe were inclined to side with Guevara. The CRRS copy belongs to a 1555 edition commissioned by a consortium of Parisian booksellers, including Vincent Sertenas, Jean Longis, and Guillaume Le Noir of Guevara’s text translated by Nicholas Herberey des Essarts, L’horloge des princes.[4] In total there were 15 French editions of Guevara’s work between 1530 and 1593, a testament to its immense popularity on the other side of the Pyrenees.[5] In this particular case, Herberay himself was known as the translator of some of the most popular novels of chivalry, such as Amadis de Gaule, and his name alone would have been enough to ensure the success of this French edition.[6]

Title pages to the same 1555 edition, in this case with the stamps of the other members of the booksellers' consortium. Above left: Centre d'Études Supérieures de la Renaissance Tours, Jean Longis, bookseller. Above right: Bibliothèque nationale de France, Guillaume Le Noir, bookseller

In Guevara’s defence against the specific charge of partaking in the corruption of the political ideals of the early Italian Renaissance, it should be said that he was hardly breaking new ground, and that the dedication of his work to Emperor Charles V––the epitome of the Renaissance prince––was merely “a continuation of the imperial humanism of Petrarch, Guarino, Biondo, and others.”[7] Indeed, although humanist discourses were now directed almost exclusively towards the princely and papal courts, the necessary shift of emphasis was not too difficult to make given that useful classical precedents could after all be Imperial as well as Republican.

[1] Ernest Grey, Guevara, a Forgotten Renaissance Author (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1973), 24.

[2] Jeremy N. H. Lawrance, "Humanism in the Iberian Peninsula," in The Impact of Humanism on Western Europe During the Renaissance, ed. Anthony Goodman and Angus MacKay (London: Routledge, 1990), 249.

[3] Grey, 97-99.

[4] “A common practice in the Paris book world was to finance an edition between a consortium of publishers or booksellers. A project would be contracted to a printer, who would be instructed to prepare copies with the names of each of the participating publishers/booksellers on the title page of the part of the edition.” Andrew Pettegree, Malcolm Walsby, and Alexander S. Wilkinson, French Vernacular Books: Books Published in the French Language before 1601 = Livres Vernaculaires Français: Livres Imprimés En Français Avant 1601, vol. 1 (Leiden Brill, 2007), ix, 713.

[5] Dandelet, 88.